Badminton: Are personal coaches better or could Indian shuttlers benefit from training in a group? | Badminton News

It’s been a slow, fraying year for Indian badminton – its first without an Olympic medal in a dozen years. Unsurprisingly, it has coincided with scant results worth noting and a breathless wait fans for assorted coaches to wave magic wands, that will throw up results, even while the athletes haven’t been in peak shape or greatest of headspaces. And while forgetting that there’s been a steady slide in the number of matches won, let alone titles secured.For the form that he went into the Olympics with, Lakshya Sen over-achieved. A semifinal finish where neither Chinese nor Indonesians made the Last 4, and a leadup where he himself hadn’t been amongst titles, will be considered creditable. For the physical preparation he had put in, and what his eclectic, clever game is capable of, losing to Lee Zii Jia was a disappointment. Especially when top coaches agree he could have even taken down Viktor Axelsen, had he kept his nerve.

The two losses from leading positions in the semis and bronze playoff, simultaneously highlight the importance of the coach in pinpoint strategy, and their helplessness in getting their players to deliver at the crunch. A coach is only as good as the results.

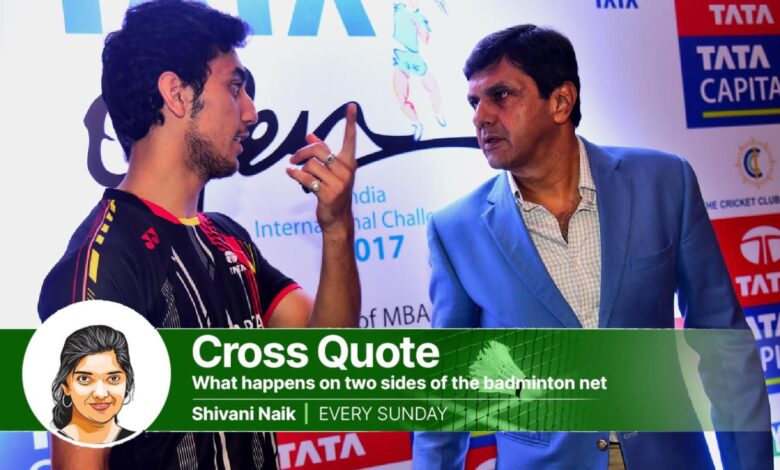

This welds into the larger, heated debate of whether personal coaches are good for the shuttlers. And being good, we solely mean whether they can get the athletes the results on the court, in sheer Ws. Wins.

For a long time, the chatter about in-bound foreign coaches, who athletes prefer for personalised attention, has been a source of mid-level annoyance for the national coach, Pullela Gopichand. It’s simply because the results have not followed in singles. And doubles went down the same route in Paris.

PV Sindhu was good for gold inTokyo but pushed herself into one right corner, dominated a coaching conundrum. Park Tae Sang wasn’t the smartest of career choices, given the nature of her game, which went into reverse with the defensive overtones. And without a second voice telling her to retain the attacking verve, and nerve. Agus Dwi Santoso was much the same – a brilliant coach for rally specials, but dimming the spark of the tall athlete’s ferocious offensive attack. Prakash Padukone couldn’t quite prop up the backsliding game, though Anup Sridhar and Lee Hyun-il will now attempt the improbable.

In hindsight, the whole world will chorus in with this insight, but Sindhu opting for a support team with a personal coach, needed the dissenting voice, even if abrasive, to get her back on track five years ago. Both Park and Agus were not particularly strict coaches, they would coax and convince and it kept her in a reasonably happy space. But they weren’t necessarily great for her game, and results.

Kidambi Srikanth blundered from one wrong call on personal coach to the next, and then the next, looking for that elusive magic-wand that could set things right. He reckoned the World Championships silver in 2021 was the formula, and continued to chase the mirage of a wonder-coach. A precociously, creative talent, all he needed was some detached honesty in telling him that physically he wasn’t at the level where he could consently trouble big names. And beautiful, bold game styles like his, needed a very strong base, to pull it off in big events, where he had a natural disadvantage in his perpetual irritation for slow courts.

Srikanth’s game was more special than the rest, and everyone from Gopichand to Parupalli Kashyap would agree. But it did not warrant special seclusion, and would have bloomed even in group sessions.

HS Prannoy put in those hard yards to resuscitate a career, albeit late in the day. But what he did not demand, as right, was personalised attention of the chief coach, simply trusting him to plan and chip in exactly when needed. Even B Sai Praneeth briefly fell into the quagmire of wanting monopolised attention and never recovered from that.

These are intelligent, highly talented and skilled shuttlers with no malice in them. Passing envy? Sure. But nothing too unhealthy. Lasting resentment? Not at all. They won India a Thomas Cup, on sheer teamwork. They bond reasonably well. But self-defeating career calls on the coaching choices? Those are plenty.

Perhaps the one male shuttler who genuinely had the right to feel ignored was Kashyap. Because Gopichand was far too focussed on taking Saina Nehwal and then Sindhu to the very top. He once even left him midway through a match at the World Championships, to tend to Saina’s game. It cost him a World’s medal, but Kashyap went on to marry the source of his grief, and the two vowed to merrily joke about it, ever after. Kashyap had the maturity to understand that Saina’s and Sindhu’s careers were headed for dizzy heights.

The one notable success was Saina Nehwal, seeking out monastic focus in Bengaluru, as she searched for an elusive World Championships medal. But Nehwal was always self-driven, and could squeeze the best knowledge out of any coach. There’s no telling if both she and Sindhu could have achieved far more had they sparred together and not chased exclusivity of attention. At any rate, they extracted plenty out of their rivalry – it added to India’s titles. But both careers eventually careened off the track, when even greater feats were possible.

Lakshya has demanded a similar bespoke, unique status with his coaching calls, though letting go of Anup Sridhar with whom he won his last title and bringing back the Korean months before Paris are debatable. And he was chastised Padukone. While it is utmost important for athletes to be happy and relaxed, they often need to step out of comfort zones where they are the centre of their universe, and len to harsh words, and feel not-so-special, so that the game gets better.

It is here that group training acquires relevance. It keeps egos in check, self-assessments are non-delusional, the sparring is infinitely better, and the feedback is diverse. Even a trivial 3v3 session, fooling around trying trick shots can pep up the drudgery and reduce inwardly-obsessed stress. Multiple coaches can offer varied insights, and it’s easier to move from one title success to the next, or one first-round exit to the next sobering failure, in the company of others traversing the same path.

The finances too work out better – one reason why Chinese and Indonesians prefer that system, and eventually even Viktor Axelsen and Anders Antonsen rejoined their national centres. Shared resources are better utilised, expertise is readily available and wheels don’t need reinventing.

Star tantrums will be tolerated as long as the success comes but the wins have gone missing recently. And though the biggest names of Indian badminton will continue to res group training, and fixate on personal coaches, they might just in heart of hearts know, that when success started trickling from 2008, it tossed up 10 different names, who each succeeded more than they do now. They thrived at a time when India boasted multiple title contenders who trained together.