Paris 2024 lessons for badminton officials: Look beyond organising tournaments | Badminton News

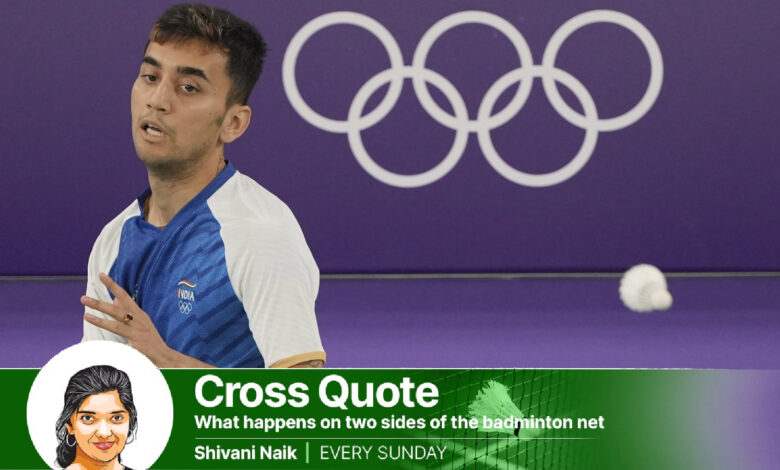

The Badminton Association of India (BAI) didn’t have much to do in matters of who represented the country at the Olympics. The Indian squad of seven – PV Sindhu, HS Prannoy, Lakshya Sen, Satwiksairaj Rankireddy, Chirag Shetty, Ashwini Ponappa and Tanisha Crasto – made it to the Paris Games because of the world rankings they had earned.BAI would wish there were 3 women in singles in the Top 16 bracket and they would have to hold trials to pick the most-likely ones to medal. But India has no such riches to boast about. And it is the lack of this happy headache that should worry those running the sport in the country.

The BAI has been lucky that the two coaching centres they support – in Hyderabad and Bangalore – have been rolling out champions. Pullela Gopichand ensured that Saina Nehwal and PV Sindhu reached the Olympic podium and now the Vimal Kumar-Prakash Padukone combination brought Lakshya Sen into the semis at Paris.

But are just two academies enough to cater to the gushing stream of young badminton hopefuls wanting to emulate the feats of Saina and Sindhu? Has BAI done enough to ride the wave that rose after India’s women shuttlers started to consently challenge the mighty Chinese? Not really.

There have been warning signs but they got ignored. India did win the women’s Asian team championship in 2024 when the likes of Ashmita Chaliha, Anmol Kharb, Gayatri Gopichand and Treesa Jolly received the leg-up in crucial team selections. But the Uber Cup this May and the 2023 Asian Games women’s team events were disasters. Sindhu could not drag a rookie team along, facing defeats herself. India couldn’t repeat the Uber Cup medal from 10 years ago, without Saina Nehwal and Jwala Gutta.

These series of setbacks should have woken up the BAI. They should have realised that they need to do more, think beyond holding domestic tournaments. They should have applied their minds to find ways to get more qualified into elite tournaments around the world.

Unlike the other stakeholders – Sports Minry and NGOs – the federations are most suited for this role. They are the domain specials. They are best placed to scout out personnel – sparring partners, specific expertise foreign coaches and Indian support staff. All NGOs would have become redundant, if the federations did this obvious job: of actually helping players get into Top 20 and fighting for spots at the Olympics.

It is all well to set the grassroots model straight first, which comes with recognising 50 more nationwide academies, and holding age-group tournaments, even enforcing a commendable age-verification system that badminton has managed. But can a federation be clueless about what to do with the nearly-there, second-string bunch and expect that medals will keep coming? Paris proved that the next step, post grassroots, was necessary.

Leave the medal prospects to the Sports Minry’s Target Olympics Podium Scheme. The federation should focus on the bunch of second-stringers who aren’t seen as medalls both the government or the NGOs. The federation gets to get solidly behind them. Take them up as projects. Maybe, call it Target Olympic Qualification (TOQ).

It wouldn’t be easy. This will need expertise, money and work. As part of their TOQ, BAI needs to plan tournaments to collect ranking points and draw out their off-season for conditioning and fitness work. They need to send a support team of physios, masseuse, trainers and national coaches to every tournament they enter.

The second-string players need to be linked up with sports science freelancers, drawing up diet charts, getting biomechanics sorted, video analysis of opponents, injury management and mental well-being besides travel and tournament entry logics.

NGOs, at times, tick all the above mentioned boxes. But then they pick and choose their winning horses and pour all the cash into 1 or 2 careers. Federations have the bandwidth to pull it off for 20-25 promising careers. And, most importantly, not all of them need to be juniors.

Akarshi Kashyap was wildly backed BAI, and went ahead of Saina Nehwal to Commonwealth Games- them having made their point of a watertight selection policy. But post the CWG, she has been left to her devices, returning to Raipur, with TOPS and NGOs not interested in what happens to her flailing fortunes.

Countless academies run former players receive support from BAI, democratising the system, and that’s only good for the sport. But a year-round mapping of preparation and performance of the second-rung, pushing for their Olympics qualification, ought to be the BAI’s job.

Almost all of India’s individual medals have come through self-driven ambitious athletes and crazy personal coaches invested in their success. NGOs and TOPS have nicely linked up, leaving federations with not much to do with elite athletes who headline medals.

Not all will obviously make it. But instead of playing second-fiddle to NGOs and TOPS, BAI could well leverage their reach, and raise an army of challengers to the prevalent stars. BAI needs to understand an important principle of grooming talent. Beyond grassroots, the saplings and plants too need investment and care.