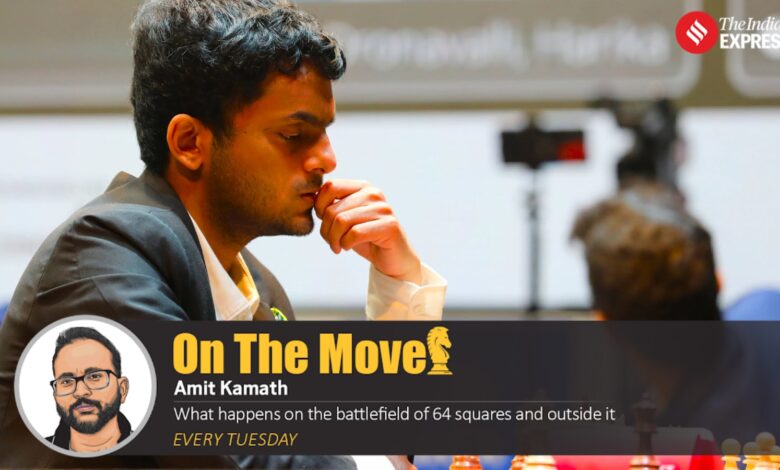

Speed demon Nihal Sarin’s career starting to gather pace again after years of slowdown | Chess News

Over the last few years, for Nihal Sarin, a speed demon on the chess board, things had started to slow down. He was one of the first prodigies from the current generation of Indian grandmasters to make headlines, especially when he became the youngest Indian to breach the 2,600-rating mark.But since he first broke into the 2,600 bracket in June 2019, he has never managed to put a foot out the door in six years (in the published rankings). Since September 2022, he has been rated over 2,650, coming close to entering the 2,700 club on more than a few occasions.

Such is the world of elite chess, especially for Indians, that staying put in one spot can feel like you’re being left behind.

Story continues below this ad

As Nihal makes a fresh bid to break into the 2,700-club — resuscitated victory at the recent Agzamov Memorial in Tashkent in an elite field that had eight players rated over 2600 — the question remains, why had one of the country’s top chess talents been moored in 2,600-club so long? Was it because he prefers to play online chess? Was it because his style is more suited for rapid and blitz events as compared to classical tournaments?

Neither is true, says his father Sarin, who explains that the problem is that at the 2600-rating threshold, chances to play against 2700+ players in closed invitational events (where organisers decide who to invite to play) is rare. With India’s burgeoning riches on the 64 squares, tournament organisers like Norway Chess and Tata Steel Chess in Wijk aan Zee can only extend invitations to so many Indians, with the first preference being players like D Gukesh, Praggnanandhaa and Arjun Erigaisi. This left someone like Nihal no invitations for closed classical tournaments.

It was a vicious circle.

But how does one get invited to play higher-rated players without at least being in the 2,700 bracket? The answer was playing in open tournaments — the wild west of chess tournaments where you don’t know your opponents, they could be a 2,300-rated GM from Serbia you have never heard of. Or a super elite 2,700+ player playing just to get some tournament practice in. This was the path that Arjun took when his inbox was in the middle of a similar drought of invitations a couple of years back.

“There were not many tournaments to play at his level. He has been at the 2,650-plus rating for the past few years now. There are very few tournaments: almost nil in India and abroad also he would have to play in tournaments where average would be around 2,300 or 2,500. Now, he’s found a few tournaments (that suit his rating). The last one was in March and before that in November, which was the President’s Cup,” Sarin tells The Indian Express.Story continues below this ad

The President’s Cup, also held in Tashkent like the recent Agzamov Memorial, was won Nihal in November 2024.

He added that his son could also play in leagues like the Turkish league, the Spanish league or the German Bundesliga. But those inevitably clash with open tournaments like the one in Sharjah, that Nihal will play in later this year.

How Arjun did it

Sarin points out that even winning a tournament doesn’t mean that organisers of super elite tournaments will knock on your doors. That’s because invitations for such events are sent to players anywhere between six months to a year in advance. This means that a single tournament win does little to sway their opinion on who to invite. The only way to catch the organisers eye then is to rack up win after win in open tournaments and raise your rating. That’s exactly what Arjun did, dueling his way out of enough open tournaments last year that he became practically impossible to ignore for the Tata Steel’s and Norway Chess’ of the world.

For Nihal, duking it out like Arjun may not come as easy.Story continues below this ad

“Nihal is someone who doesn’t go out and dominate in open tournaments. That’s not his style of play. He’s not someone who takes outrageous risks,” explains Srinath Narayanan, the man who shaped Nihal — and Arjun too — as one of his earliest trainers.

Srinath adds: “It so happened that Nihal came up in an era where there were so many different prodigies that the only way for him to get into a higher level was through these open tournaments. In a previous generation, he might have been the only prodigy and consequently played in all the invitationals.”

Srinath, who was the captain of the Indian Olympiad team which was glaringly missing Nihal but won the gold at Budapest last year, believes that Nihal is far from his prime.

“He can definitely play well in classical format. He just happens to be more known for his faster time control due to playing a lot online primarily. Sometimes taking a certain level of risk comes a bit easier in the shorter formats because he doesn’t have a lot of time to think and second guess those things. But that’s also something he can overcome in the classical format as well. But it does feel like he is working hard to do better in open events. He had a pretty topsy-turvy game against Sanan Sjugirov in Tashkent as well. I feel that he is making a very conscious effort to improve on these aspects and the results are starting to show,” Srinath says before adding: “I feel Nihal is still quite far from his full potential.”Story continues below this ad

And that should send alarm bells blaring in countries around the world that are currently fixated on the trio of Gukesh, Arjun and Pragg.